New EU Design Regulation can kill your infringement claim

08/01/2026

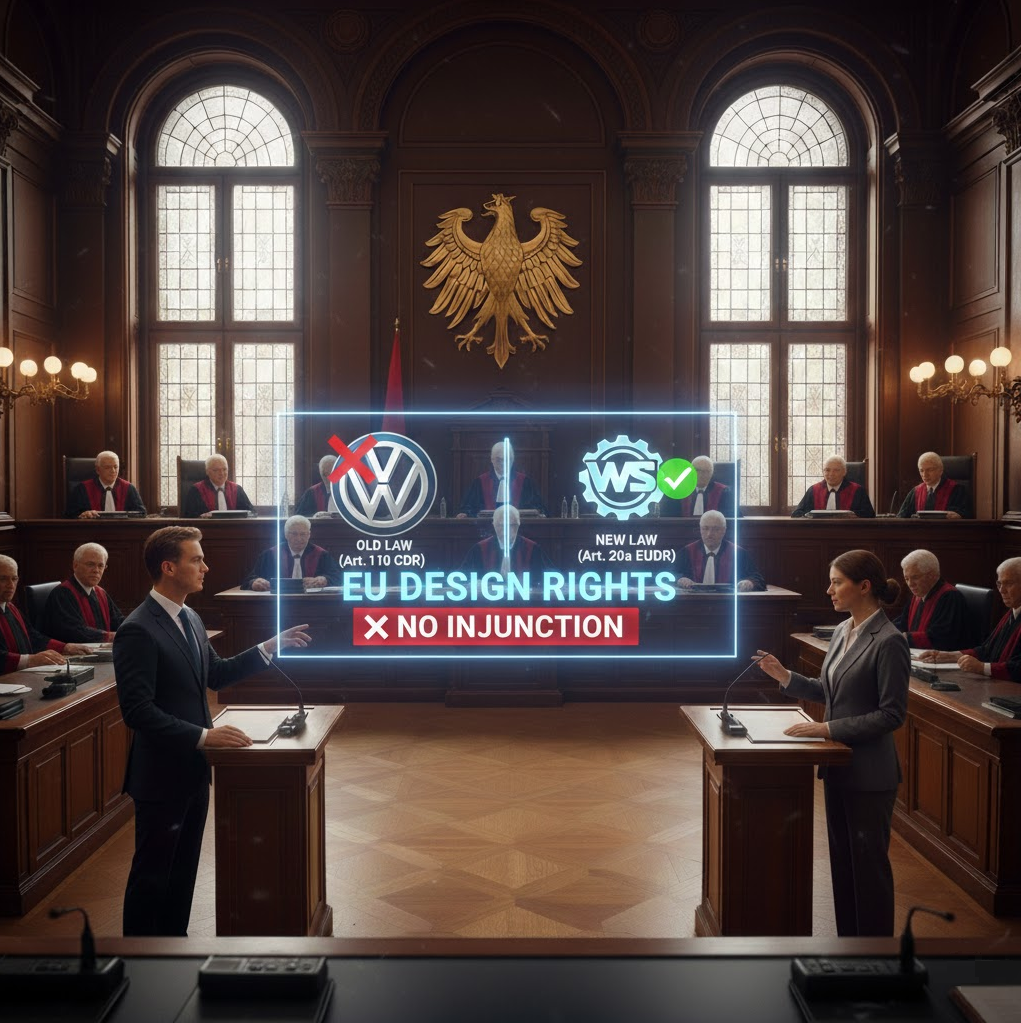

The decision in case I ZR 116/24, delivered by the German Supreme Court, is a landmark ruling that demonstrates how changes in EU design law can directly affect the outcome of infringement actions. The case shows that even when infringement is established, procedural and transitional legal issues may deprive a design owner of effective remedies such as injunctions.

Factual Background of the Dispute

The dispute arose between Volkswagen, the proprietor of a registered EU design protecting the external appearance of a car key housing, and W+S Autoteile, a company engaged in selling replacement key housings. Volkswagen alleged that the replacement housing sold by W+S was visually identical or highly similar to its registered design and therefore constituted design infringement.

Volkswagen succeeded before the lower courts, and W+S also failed in its challenge to the validity of the registered design. However, instead of contesting similarity further, W+S relied on a statutory defence—the repair clause—arguing that its product was a spare part intended to restore the original appearance of a complex product and was therefore exempt from design infringement liability.

Why Both Old and New Laws Applied

A crucial procedural rule under German law requires that an act must be unlawful both at the time it was committed and at the time the judgment is delivered. Because the alleged infringing sales occurred before and after 1 May 2025, the date on which the new EU Design Regulation (EUDR) entered into force, the Court was required to assess infringement under:

Article 110 of the Community Design Regulation (old law), and

Article 20a of the EU Design Regulation (new law).

This dual assessment placed the Court in the difficult position of applying two different legal standards to the same commercial conduct.

Assessment Under the Old Repair Clause (Article 110 CDR)

Under the former Article 110 CDR, the repair clause applied where a spare part was used to restore the original appearance of a complex product. The Court accepted that the replacement key housing sold by W+S fulfilled this basic requirement, even though it also had an aesthetic function and was visible during normal use.

However, the old law imposed strict consumer information obligations. Sellers were required to clearly inform consumers that the spare part was not an original product and was intended solely for repair purposes. The Court found that W+S failed to comply with these obligations. As a result, despite being eligible in principle for the repair clause, W+S lost the benefit of the defence and was held liable for design infringement.

Consequently, Volkswagen was entitled to damages and disclosure of sales information for infringing acts committed up to 30 April 2025.

Assessment Under the New Repair Clause (Article 20a EUDR)

The new Article 20a EUDR significantly narrows the scope of the repair clause. It applies only where the spare part is strictly form-dependent, meaning that its shape must be dictated entirely by the need to fit or match the original product. The Court held that the car key housing did not meet this requirement, as its design was not technically or functionally dictated by the key itself.

In addition, the new regulation introduces even more stringent information requirements, which W+S also failed to satisfy. As a result, the repair clause was entirely unavailable to W+S under the new law.

Refusal to Grant Injunctive Relief

Despite finding infringement under both legal regimes, the Court refused to grant an injunction preventing future sales. Under German procedural law, injunctions depend on a presumption that the infringer is likely to repeat the unlawful conduct. The Court held that the change in law itself constituted a “special reason” sufficient to rebut this presumption.

According to the Court, because the new law was stricter, W+S was unlikely to commit future infringement. This reasoning led the Court to deny injunctive relief, even though the past conduct was unlawful and the repair clause was unavailable under the new regime.

Denial of Destruction of Goods

Volkswagen also sought an order for destruction of the infringing key housings. The Court rejected this request, holding that destruction would be disproportionate, particularly in light of the regulatory transition and the absence of an injunction.

Legal and Practical Implications

This judgment highlights a serious enforcement gap created by the interaction of substantive EU design law and national procedural rules. Although infringement was established both before and after the legal reform, Volkswagen was denied the most effective remedy—an injunction. This outcome raises concerns about consistency with Article 89(1) EUDR and Article 130(1) EUTMR, which envisage injunctions as the primary means of protecting intellectual property rights.

The Court’s assumption that future infringement would not occur appears contradictory, as W+S was found non-compliant under both regimes. If that assumption proves incorrect, Volkswagen may be forced to initiate fresh litigation, undermining legal certainty and effective rights enforcement.

The decision demonstrates that under the new EU Design Regulation, winning an infringement case does not guarantee meaningful relief. Transitional legal periods can weaken enforcement, and procedural doctrines may override substantive findings of unlawfulness. The ruling leaves unresolved questions about how EU design protection should balance legal certainty, procedural fairness, and effective remedies, making it a cautionary precedent for design owners across the European Union.

Mahima